An interview of Antonio Iannibelli, an Italian expert of wolves, photographer, and author. Interview by Brunella Pernigotti a Wolves of Douglas Co WI News Media & Films’ Italian Writer.

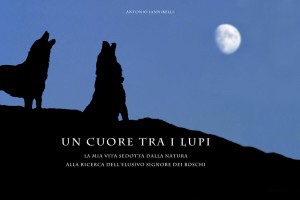

Click the following highlighted words for more information on Antonio Iannibelli’s book A Heart Among the Wolves by Antonio Iannibelli

Antonio Iannibelli’s website Ethics and Naturalist Photography by Antonio Iannibelli

The Full Interview of Antonio Iannibelli by Brunella Pernigotti

Q: In few words could you please introduce yourself and describe what you are doing about the advocacy of Italian wolves?

A: I’m not a scientist or a public administrator, neither am I a hunter or a researcher: I’m just a private citizen who loves photography and nature and who has been spending his free time for many years tracking the Italian wolves of the Apennines.

A: I’m not a scientist or a public administrator, neither am I a hunter or a researcher: I’m just a private citizen who loves photography and nature and who has been spending his free time for many years tracking the Italian wolves of the Apennines.

My grandfather was a shepherd and when I was a child he taught me many lessons that are still helping me to track the wolves and to understand the secret of their success. I try to describe the wild wolves simply by means of my photos, I use the immediate effect of images to document some stories with a realistic language. I try to be neither too technical nor poetical. I would like to help to spread correct information about Italian wolves so that once people really know them, they won’t be able to hate these animals anymore.

Q: You were born in the heart of “Lucania” [Lucania, the modern Basilicata, means “The land of wolves” in the ancient dialect] and you have been travelling throughout the mountains of the Apennines since you were a child. From a geographical point of view, Italy is shaped like a T, with the Alps that edge it in the north and the Apennines; which are a sort of back-bone placed lengthwise from the north to the south. Now, we know that over the past centuries the Canis Lupus Italicus never became extinct in the Apennines. On the contrary in the Alps it was persecuted and the whole population was killed off. Then in the last century when, in the Seventies, wolves came back and naturally repopulated the Alps. What are the reasons of this difference, in your opinion?

All Photographs of wolves for this interview are by by Antonio Iannibelli

A: Yes, it’s true. I spent my childhood with my grandparents, shepherds and farmers, in the great “house” of Bosco [Wood] Magnano, that is situated in the heart of Pollino Park, in Basilicata. I loved studying wild animals much more than my school lessons, so my parents weren’t very indulgent. However, it was my grandfather that looked after me, and he himself had been born in a family of shepherds and hunters. My grandfather knew nature very well, and was an exceptional expert of big predators, such as wolves and eagles.

“I’m not a scientist or a public administrator, neither am I a hunter or a researcher: I’m just a private citizen who loves photography and nature and who has been spending his free time for many years tracking the Italian wolves of the Apennines.” ~Antonio Iannibelli

The Alps and the Apennines have a very different habitat, but you know wolves have a great ability to adapt and they can live well in both the places. The persecution from the hunters was more serious in the Alps. In the Alps there aren’t so many woods, and in winter the snow covers the ground for a longer period of time: these elements expose the wolves to greater risks, as they are traceable more easily, and the food is less available. Even the neighboring countries [France, Switzerland, Austria] are not much help, because they provide more exceptions to the international rules that should protect the wolves. Finally, the great biodiversity of Apennines and the morphology of their ground are the most proper house to our Canis Lupus Italicus. In fact, above all in the Central-Southern Apennines, our wolves have always been able to find more wild prey, and safe dens where they can breed their pups. Whilst, in the Alps the environment is less propitious.

Q: As far as I know, even the current wolf management is different in the Apennines, where it seems to be more fragmented than in the Alps, and it varies a lot from region to region. Do you think it’s true? And to what extent?

A: In Italy the wolves are protected according to a law which is the same in the whole state territory, but in the Alps there are some autonomous regions and provinces that sometimes ask and tries to receive approval to kill a controlled number of wolves per year: of course they do it for political and economic interests. However the situation is different among the other regions, too, and the reason is always the same: managing the wolves entails a lot of economic interests. In my opinion giving too much autonomy to our regions is not a good choice, and the International Rulebook adopted by Italy should discipline the wolves protection from the top, and by means of definite and clear rules.

Q: In your book you describe the experiences you’ve had from childhood up to now on tracking wolves. You illustrate when you used to go to herd the livestock with your grandfather. My question is: was he a particularly wise and enlightened man? Or did everybody in his village have his same belief; that wolves are not enemies, nor an obstacle to get rid of at all costs? And now, how do these stockmen feel about the present wolf management since they are the most exposed to coexistence with wolves?

Q: In your book you describe the experiences you’ve had from childhood up to now on tracking wolves. You illustrate when you used to go to herd the livestock with your grandfather. My question is: was he a particularly wise and enlightened man? Or did everybody in his village have his same belief; that wolves are not enemies, nor an obstacle to get rid of at all costs? And now, how do these stockmen feel about the present wolf management since they are the most exposed to coexistence with wolves?

A: My grandfather was strongly related to his territory and to his livestock: he supported his family working hard and he knew that the flock had to be protected and watched particularly against bandits who were very popular: in those days before and after the Second World War. That’s why he thought that the true problems were not the wolves, and that watching carefully the flock and owning good watchdogs was enough to keep wolves far away. In those days, then, it was common opinion to think wolves as useful animals, too: for example, when a tame animal died in the mountain woods it was hard to be found and buried, so it became food for wolves that prevented, in that way, the spreading of diseases. “Luckily there are wolves!” my grandfather was used to say. Usually this happened most often during the seasonal transhumance, when thousands of sheep went down from the mountains to the seaside. There were many missing, unwell, or injured animals that couldn’t be carried as the shepherds set out on the journey walking on old and steep sheep-tracks. Still today the few existing shepherds of my mountains consider the wolf as a useful animal with a great ability to survive: wolves are brainy and they can steal some sheep from some inexpert shepherd, but after all wolves prefer feeding on waste to risking a gunshot. It’s a kind of unwritten agreement between men and wolves which is respected from time immemorial.

Q: In spite of the European directives that provide the protection of wolves, these animals are often victims of poaching. Considering the recent public funding cutbacks, do you think the Italian forest rangers have the appropriate resources to fight against this serious problem?

A: I think that they have the needed tools and the resources, but often the will and the coordination of every force are not completely put into the field. Poaching in Italy is a plague out of control, not to mention the lack of information and coordination in the research and, finally, the want of the right tools to prevent wolves crashing against the various means of transport. Speaking of which, we know that a great number of wolves (and not only wolves) are killed being run over on roads, railways and even on protected areas paths (such as the recent case of the wolf killed in the Oasis Castel di Guido, near Rome). Roads should be made safer places by means of specific over-and-under-passes for wild animals, as it happens in other European countries, such as Austria and Germany.

“When, during a magical night, I saw a wolf beside me, I thought I had really become a wild creature, too.” ~Antonio Iannibelli

Q: Let’s talk about hybrids and grown-wild dogs. They seem to be a big problem in the Apennines, whilst in the Alps anybody hasn’t yet caught sight of them. Could you please explain why?

A: As I told, the harder climate of the Alps doesn’t allow domestic animals to survive, so abandoned dogs die in few days; on the contrary, they can live and reproduce particularly in the Southern Apennines, where you can spot also goats and pigs gone wild. Therefore I think that the bad practice of letting dogs free to roam in the woods in Southern Italy is at the main cause of this problem that affects wolves when they come in contact. In the ridge of Apennines there are some packs of hybrids that reproduce. In Italy today we have some projects to monitor the wild hybrids (only a few dozen) but I think that a close watch on the abandoned and stray dogs (several thousands) would be enough. However, the wolves that live in the wilder areas of the Apennine ridge prefer attacking and eating to mating stray dogs that invade their territories.

Q: In your book you describe a lot of impressive encounters with these elusive and mysterious animals. Would you tell us the one you remember best?

A: Every encounter with a wolf is somehow a miracle: it’s Nature that appears in its wild sacrality. When, during a magical night, I saw a wolf beside me, I thought I had really become a wild creature, too. When I was a child, I used to ask my grandfather to show me the wolves, and he wisely answered that I would be able to see them on condition that I became a sort of wolf, too. But, at that time, I often disbelieved my grandfather, and even the existence of wolves.

It was in autumn and I had got up in the middle of the night hoping to see the Monte Sole [Sun Mountain] pack. I was hidden in my usual place, waiting in silence for the new day, when I heard the bumps of two fighting deers. I grabbed my binoculars, but was still too dark to see the two fighting males. Even though I couldn’t see off to the side of me, I felt I was being watched so I turned instinctively. The more my eyesight adjusted, the more I realized that there was a wolf by my side: obviously the clashing antlers hadn’t attracted just my attention. The enchanted place, the magical night, the wolf by my side, that was watching the same event I was; reminded me of my grandfather’s words.

Q: The wolves are the symbol of wild life and freedom for many of us. How much is it worth the life of even one of them for the future generations?

A: The wolf’s survival is the same as ours itself: killing even only one of them means robbing the environment of one useful part that keeps it complete. If we don’t make an effort now to defend wolves, in the future our children won’t be able to enjoy a healthy territory such as the Apennines, where there is such a great biodiversity.

Q: Are young people educated enough on how to protect the ecosystem where they live?

A: No, they aren’t. Unfortunately the future environmental education depends on our choices, too. Nowadays this subject is still very uncommon in the Italian schools.

Q: Wolves Of Douglas County Wisconsin promotes education and awareness to practice the preservation, and especially coexistence, based on empathy and the elimination of every kind of violence, the verbal one, as well. It supports and shows how much every wild species is worth; it’s against hunting, trapping, and practices the use of non lethal methods for the farmers to defend their livestock. Is there something like it in Italy? What are we doing?

A: Unfortunately we are not doing enough: as I told you before, the supervision is insufficient to reduce the conflicts with the farmers, who tend to take the law into their own hands, because they want to avoid the slow bureaucracy; the interventions which are often insufficient. Evert year more than 100 wolves are intentionally killed (shot, poisoned or trapped) and many are victims of the human presence, e.g. they are run over on roads and railways. In these last years the persecution of the wolves has increased. With the help of a group of friends, I realized a project of monitoring the causes of death of the Italian wolves Lupi morti in Italia Facebook Page It confirms this trend.

Q: Are the Italian farmers adequately informed of the non-lethal deterrent systems to defend their livestock?

A: Again, there is a great difference between the Alps and the Apennines, between the north and the south of Italy. In the north there is more awareness; but there are also more difficulties to use these means to protect the livestock because of the morphology of the area, and the extent of the rangelands. In the northern Apennines the farmers are well informed, but the situation is different from Region to Region: in Emilia-Romagna for instance there is a better situation than in Tuscany, where there are some farmers who refuse to use any deterrent, and would like to definitively remove the wolves. In the south of Italy, on the contrary, the situation is better because the wolves have always been there and the farmers never let their livestock be unattended. In those places they don’t need any electrified fence or sonorous deterrent because the farmers coexist with the wolves from time immemorial. Besides the less rough area and the more temperate weather help the animals watch. Also here we can have some cases of poaching, but the guard dogs are very efficient and keep wolves away, so they must make do with the wastes of the cattle sheds or the remains of the butchery.

A: Again, there is a great difference between the Alps and the Apennines, between the north and the south of Italy. In the north there is more awareness; but there are also more difficulties to use these means to protect the livestock because of the morphology of the area, and the extent of the rangelands. In the northern Apennines the farmers are well informed, but the situation is different from Region to Region: in Emilia-Romagna for instance there is a better situation than in Tuscany, where there are some farmers who refuse to use any deterrent, and would like to definitively remove the wolves. In the south of Italy, on the contrary, the situation is better because the wolves have always been there and the farmers never let their livestock be unattended. In those places they don’t need any electrified fence or sonorous deterrent because the farmers coexist with the wolves from time immemorial. Besides the less rough area and the more temperate weather help the animals watch. Also here we can have some cases of poaching, but the guard dogs are very efficient and keep wolves away, so they must make do with the wastes of the cattle sheds or the remains of the butchery.

Q: Finally, besides asking you if there is something else you would like to say, I have for you the question that I always ask in my interviews: what did the wolves teach you, during your life?

A: I’d like to add at least one thing: more than 15 years ago I created an event “The wolf celebration” (Festa del lupo 2018) in order to give correct information to the common people about the Italian wild wolf: it is a no profit event and it’s aimed to oppose the false stories that media propagate every day. Next biennial festival will be held from 2nd to 4th November 2018 at Castello Manservisi, in Castelluccio di Porretta Terme: http://castellomanservisi.it/wordpress/ All of you are invited!

What did the wolves teach me? It’s a good question. They taught me to live in harmony with nature, to respect every creature and, above all, not to waste our resources. My whole life has been influenced by the wolves, maybe because I was born in Lucania: this old name for Basilicata means “The Wolf’s Land” and it has an ancient Greek origin: λυκος [lukos]means wolf, even so my grandfather never told me false stories about the bad wolf. Watching their behavior taught me to be sincere and to do everything without asking anything in return, just as they do. Even though we persecute them, the wolves carry out their task which is essential for our survival, too. The wolves have learnt the meaning of coexistence . We haven’t!

Thank you very much for the time you devoted to us. Brunella

Photograph is the book cover of Antonio Iannibelli’s book A Heart Among the Wolves by Antonio Iannibelli

Thank you Antonio Iannibelli for this interview! Then, since you are a naturalist photographer and an Italian expert of wolves, let’s make a list of your activities for our readers so they can read them on the Internet:

A blog on Italian wild wolves : http://italianwildwolf.com/info/

The bill of rights of the wolf : http://italianwildwolf.com/carta-dei-diritti-del-lupo/

Your book “A heart among the wolves”: http://antonioiannibelli.it/un-cuore-tra-i-lupi/

Your book trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rUq_AATOQ3A

Ethics and naturalist photography: http://antonioiannibelli.it/2016/02/11/etica-e-fotografia-naturalistica/

All the photographs of Italian wolves copyrighted by Antonio Iannibelli

__________________________________________________________________________________________

About Brunella Pernigotti

I am a lover of wolves and of Nature in general. With the means of knowledge and awareness, I try to devote myself to the protection of the environment and of the endangered species, as far as I can do. I live in Turin, Italy. I’m a teacher, a writer and a photographer. I published a novel and a book of tales and have to my credit about ten one-man exhibitions of photos. I’m member of the board of a no-profit association of Turin, “Tribù del Badnightcafè”, that organizes cultural and artistic events. Besides I created a group of volunteers to help women who are victim of domestic violence.

I am a lover of wolves and of Nature in general. With the means of knowledge and awareness, I try to devote myself to the protection of the environment and of the endangered species, as far as I can do. I live in Turin, Italy. I’m a teacher, a writer and a photographer. I published a novel and a book of tales and have to my credit about ten one-man exhibitions of photos. I’m member of the board of a no-profit association of Turin, “Tribù del Badnightcafè”, that organizes cultural and artistic events. Besides I created a group of volunteers to help women who are victim of domestic violence.

Leave a Reply